Artificial intelligence has to date been enlisted as a bogeyman in cultural circles: Software will take the jobs of writers and translators, and AI-generated images ring the death toll for illustrators and graphic designers.

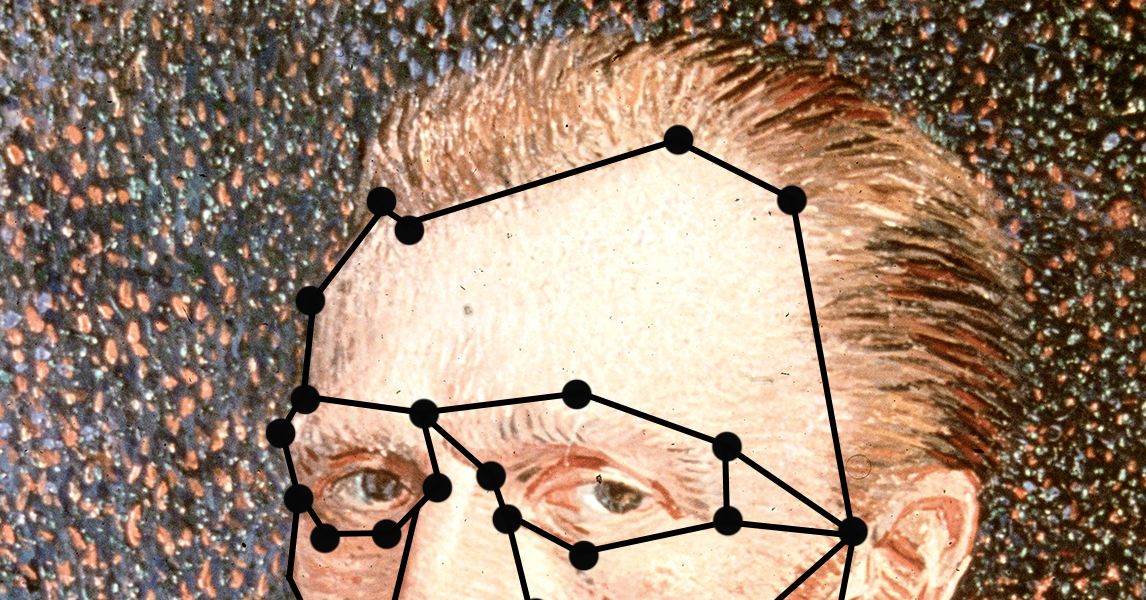

Yet there’s a corner of high culture where AI is taking on a starring role as hero, not displacing the traditional protagonists—art experts and conservators—but adding a powerful, compelling weapon to their arsenal when it comes to fighting forgeries and misattributions. AI is already exceptionally good at recognizing and authenticating an artist’s work, based on the analysis of a digital image of a painting alone.

AI’s objective analysis has thrown a wrench into this traditional hierarchy. If an algorithm can determine the authorship of an artwork with statistical probability, where does that leave the old-guard art historians whose reputations have been built on their subjective expertise? In truth, AI will never replace connoisseurs, just as the use of x-rays and carbon dating decades ago did not. It is simply the latest in a line of high-tech tools to assist with authentication.

A good AI must be “fed” a curated dataset by human art historians to build up its knowledge of an artist’s style, and human art historians must interpret the results. Such was the case in November 2024, when a leading AI firm, Art Recognition, published its analysis of Rembrandt’s The Polish Rider—a painting that famously confounded scholars and led to many arguments as to how much, if any of it, had actually been painted by Rembrandt himself. The AI precisely matched what most connoisseurs had posited about which parts of the painting were by the master, which were by students of his, and which involved the hand of over-enthusiastic restorers. It is particularly compelling when the scientific approach confirms the expert opinion.

We humans find hard scientific data more compelling than personal opinion, even when that opinion comes from someone who seems to be an expert. The so-called “CSI effect” describes how jurors perceive DNA evidence as more persuasive than even eyewitness testimony. But when expert opinion (the eyewitnesses), provenance, and scientific tests (the CSI) all agree on the same conclusion? That’s as close to a definitive answer as one can get.

But what happens when the owner of a work that, at first glance, looks totally inauthentic to the point of being laughable, recruits a slick firm with the task of gathering forensic evidence to support a preferable attribution?

Lost and Found

Back in 2016, an oil painting surfaced at a flea market in Minnesota and was bought for less than $50. Now its owners are suggesting that it could be a lost Van Gogh, and therefore would be worth millions. (One estimate suggests $15 million.) The answer—at least to anyone with functioning eyeballs and a passing familiarity with art history—was a resounding “nah.” The painting is stiff, clumsy, utterly lacking the feverish impasto and rhythmic brushwork that define the Dutch artist’s oeuvre. Worse still, it bore a signature: Elimar. And yet, this dubious painting has become the center of a high-stakes battle for authenticity, one in which scientific analysis, market forces, and wishful thinking collide.

The owners of the “Elimar Van Gogh,” as it has come to be derisively known in art circles, are now an art consultancy group called LMI International. They are investing heavily in getting experts to say what they want to hear: that it is, in fact, a genuine Van Gogh. This is where things get murky. The world of art authentication is not a straightforward affair. Unlike the hard sciences, art history deals in probabilities, connoisseurship, and competing expert opinions. It is also, crucially, an industry driven by financial incentives. If the painting is deemed real, its value skyrockets. If it’s deemed a fake, or rather in this case a derivative work by someone named Elimar who daubed a bit on canvas, distantly inspired by Van Gogh perhaps, but with none of his talents, it’s virtually worthless—about as valuable as you might expect to find at a flea market in Minnesota for under 50 bucks. This imbalance in stakes has led to a dangerous trend: hiring experts not to determine authenticity, but to affirm it.